If you’d like, you can listen to an audio version of this page. It includes all the contextually relevant bits of music, and a few ad libs not included in the text. But it doesn’t include the links and images, naturally.

In 2010 I quit my job to make indie games.

My childhood friend Sterling had just finished studying comp sci at university, and I’d talked him out of going straight into the industry. Big teams, no autonomy, no vision.

He was a graphics programming savant, deeply specialized, and I could do all the other stuff. Together, we were T-shaped. We had a shared appreciation for weird, innovative games. And we each had some savings.

This was before Steam Greenlight. Before Indie Game: The Movie. The paint was still drying on the App Store. The iPad was new and nobody knew what to do with it. Maybe this big portable screen would be a great canvas for games. Hell, any day now, Flash should come to iOS. But if it doesn’t, Unity seems promising, if a little restrictive.

It feels like indie games are right on the cusp of exploding, the way indie music had a few years ago.

World of Goo and Braid were surprise hits — people had an appetite for quirky, systems-driven games. Online, other indie devs were buzzing about “procedural content generation”. With just one or two clever programmers, you could make a system to generate all the art and levels and music for a game, what would normally take a whole team to produce. You could even make a system that’d underlie your gameplay, letting you tap into new kinds of physics and feelings, breaking away from traditional genres. Could we do that?

The first game we tried to make was, almost exactly, Jusant — a game where you climb up a babel-like tower, stretching from the ground to the sky, through the clouds, so high that by the end there’d be no gravity holding you down. We’d referenced Assassin’s Creed and Metal Gear Solid 2, how they each so differently used the feeling of climbing way up high around the outside of a building. The sounds of the bustling city below fade away, overtaken by a stirring wind. Any interior passages would be a relief, a moment of shelter from the elements and the fear of falling, but with risks of their own. And then back out, and up.

There’d be grapple points and hanging ropes, things to swing on, ladders and jutting rocks, narrow walkways. Crumbling abandoned huts built into the rock face, ripped nets, other materials that’d vary as you ascended. There’d be no combat, maybe no other people at all — just climbing. Just the feeling of climbing, that thrill of moving deftly through a complex world (Mario, racing games) or the interplay between the space and your body (Metroid, Mirror’s Edge).

That idea sucked. We couldn’t procedurally generate the tower — it’d need to be hand-authored. Doing procedural character animation for climbing seemed impossible. Hell, Assassin’s Creed was just a really complicated system blending hundreds of hand-authored animations.

The next game we tried was A Shrinking Feeling. I wanted to do what Braid did — a clever twist on a classic, where you realized something was possible, hell it was simple, it was right there and nobody had done it, you could do it, you just have to be careful and do it really well, really think about what has just changed, what you can do with it, what it might mean. Braid took something that’s an implicit assumption in games — time moves forward at a steady rate — and asked, “What if it didn’t?” So I took this idea and generalized it by one step.

There are things you assumed were constant, but what if they aren’t?

What other constants exist?

Scale.

In this game, your character is shrinking. Always shrinking. Sometimes faster, sometimes slower. Always shrinking. Forever.

The world around you feels familiar right now, but just wait a minute. That little enemy you could have squashed, no problem, is now quite the looming threat. But that little squiggle in the ground below you is now a crack, and then a cave, and then a cavern, and you can duck down into it to escape. You are always shrinking. The world around you, and everything in it, is always growing.

These ideas don’t belong to any particular genre. But we needed to pick something to build around. So, we started with the classic: 2d side-scroller. Mario, Sonic… yeah, Braid too. But we could imagine generating these worlds procedurally. We could make a system. I’d draw little bits of the world as paths (not pixels), so that we could snap them together and scale them up and subdivide them into smaller fragments. We could texture them so that as you shrunk, the levels would go from looking normal and Earthly to microscopic to wildly abstract and impossible.

Sterling worked on a prototype of the game. He got something playable, and it was kinda fun! I made some placeholder art, and was working on bits of narrative, and then… and then…

There are things you assumed were constant, but what if they aren’t?

Music! I realized that this idea, you could do this with music, too! And, of course, the constant that could grow or shrink, that would perfectly fit with the tone and idea of our game, was tempo. The music would slow down forever. As it slowed, notes would be spaced further and further apart, creating little gaps to be filled by tiny new melodies and rhythms.

I prototyped a system, a little music system, in Unity, and it worked!

That plan sucked. We figured it’d take us months, maybe a year or more, to make this game any good. We didn’t have enough money.

So we put it aside, and tried to make something else. Something simple, that we could make and release within a month, hell, a week, just to prove that we could. We made it. And it was… fine. But we never released it. We grew to resent each other and, due to the very human emotional mess of it all, with its many complications (like, say, the fact that I was dating his brother), Sterling and I parted ways… almost amicably. I went back to my old job. He went off and worked at big tech companies (eventually joining Apple Vision around the time it was just getting started).

But I couldn’t let go of this idea.

There are things you assumed were constant, but what if they aren’t?

In 2012, I was making a little home for myself in the sound art scene. There was a program director at a major performing arts center who became quite fond of my systems. She kept feeding me opportunities to exhibit and perform and mingle with other artists. It felt like she was almost just handing me a new career.

All of it was this shrinking music.

I came very, very close to quitting my job (again) to make a career of this sound art stuff. But… all of these gigs involved signing contracts, and these contracts came with exclusivity rules.

For instance. I’d been invited (by a different program director at a competing performing arts center, haha) to join an experimental dance troupe to develop a new show. We’d rehearse for a few months, full days, 6 days a week. We’d do a run of shows locally, and then go on tour. But the local run of shows coincided with a sound art festival at the other place. I’d already been booked to perform there. And this was against the rules.

We’re putting your name on the bill, which means people are coming to see you. That means you can’t be on another bill elsewhere in town at the same time, because that’ll split your audience, and we won’t sell as many tickets.

That deal sucked. I did the math and, at the rate I was booking gigs, and for how much these gigs paid, and for how much time they’d take, and for having to quit my current job to put that time in… I wouldn’t make it. I didn’t have enough money.

I stopped doing sound art. I moved out from the city, to live with my girlfriend in a condo at the edge of town. It was a condo, so I couldn’t make any music. My last album — unfinished, at that — is from 2014.

But I refused to let go of this idea.

There are things you assumed were constant, but what if they aren’t?

In 2016 I was learning more and more about coding. Watching Strange Loop talks. Building stuff in the browser. (Flash was not coming to the iPhone, sigh.) Picking up ClojureScript.

I rebuilt the shrinking music in ClojureScript, in the browser. It sounded great. I loaded it up with samples from my last few albums, so that it sounded rich and textured and grounded in reality. I didn’t just make it go slower forever, or faster forever — I gave it a custom function, interacting sine waves generating accelerations that’d pull it back and forth like an infinite series diverging into the horizon.

But that was it. A little side project.

Life slowed down.

I moved away from the city. Slower.

I built a house in the woods. Slower.

I had a kid. Much slower.

I make computer programs,

and that’s about it. To a crawl.

That’s the version of me you probably first met.

There are things you assumed were constant, but what if they aren’t?

I am tired of being a computer programmer. I am tired of writing code. It is a grid of letters. It is monospaced. It does not move. You cannot make it shrink and grow, stretch it out, squish it together. Well… maybe you can. You just have to get away from static text. You need to be in an environment where it makes sense for things to shrink and grow, for cracks to open up that you can slip down inside.

And I am bored of not making music.

A friend of my mother’s, a widow whose husband used to play professionally, is getting rid of a beautiful old upright piano. An elderly man, a retired church pastor, is selling the beautiful antique pump organ from his old church.

I have all these instruments.

I have a few remaining microphones that aren’t broken.

I have the weekend to myself once in a while.

I’ve started noodling again.

Jerk (Improv)

I’ve started turning these noodles into tunes.

Jerk (Progression)

I’ve started normalizing sharing.

One thing I’ve always wanted to do is record some of this shrinking/growing music with real instruments.

I tried a few times. In Ableton Live, my music software of choice, you can control how different parts of the sound should change throughout the course of a song. You can make the volume go up and down, or bring in some echo right when you need it. You can also control the tempo! You draw a graph showing how the tempo should change. You can make the change sudden, or you can make it gradual.

Live’s tempo control sucks. It updates these values in small little steps, each step the size of a 32nd note. Every time it takes one of those steps, you can hear a little pop or glitch from the changing tempo. (Ableton heads: this seems to happen even if you’re not using warp modes. It’s fucked up.)

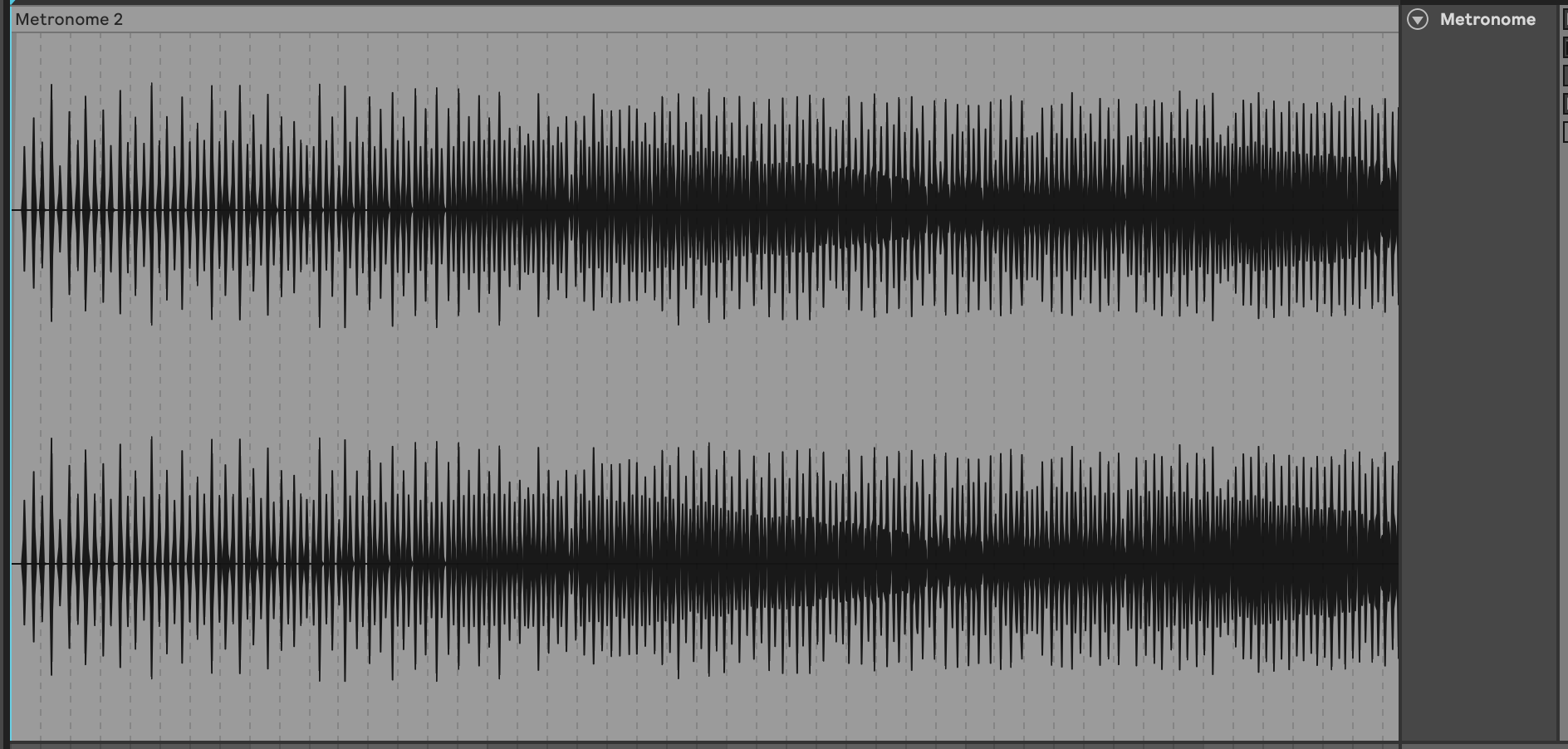

So instead of relying on this broken tool, I just made my own. I took my old ClojureScript shrinking music program, and turned it into a metronome.

I recorded that metronome into Ableton Live, so that I could listen to the sound of something smoothly speeding up forever and record along with it.

Speeding up, yes. I’d tried it both ways. I knew how they each felt. Slowing down is sedate. Contemplative. I wanted to shake out the cobwebs. I wanted to go faster. I wanted that thrill of moving deftly through a complex world, the interplay between the space and my body.

In early March, I had the house to myself for a few days. I recorded piano, and drums, guitar, and bass.

For every layer, I’d hit record and start playing along… slowly at first, and the metronome would get faster, and I’d play faster. And it’d keep getting faster, and I’d keep playing faster, until I started to make mistakes. And I’d keep playing faster, and the mistakes would compound, and the sounds would smush together until I was playing total nonsense, and the rhythms would drift out of alignment until I couldn’t keep up at all. Hit stop.

Then I’d pick up a different instrument, and start recording again, a little later on in the song when things were already fast, but I’d start relatively slowly — half time, quarter time.

After I had a bunch of layers, I started mixing them together. EQ. Compressor. Reverb. Gain. I’d turn each layer down until you could barely hear it. Hide all the sounds behind each other. Every sound in the song is hidden behind the song. In psychoacoustics, this is called “masking”, and I love doing it.

I noticed that this song was… fun. You could loop a few bars, and they’d ever so slightly push and pull at your feeling of time. Then loop the next few bars, and they’d do it again. So that’s how I worked — advance the loop, fix the sound, advance the loop, fix the sound, advance the loop, fix the sound…

(I don't know why I look so angry in that video. I was feeling good. Maybe just concentrating.)

The song was taking shape.

It had a weird B-section, and I kinda liked it, but it wasn’t quite working. When I record a song, I usually like to try at least one or two new ways of playing an instrument. This song has two.

- First, the kick drum hits all coincide with a staccato blast of bass from the pump organ — a technique I picked up from Louis Cole, an incredible drummer who uses his left hand on a keyboard to play basslines in sync with his kickdrum. Of course, my drum kit and pump organ are in separate rooms, and not easily moved, so I had to record them separately. That was a chore, but I love how it turned out.

- Second, there’s a distorted bass guitar. You don’t hear distorted bass all that often, and the song already has a pretty thick low end from the pump organ, so I figured some crunchy bass guitar would sit nicely in the low-hundred Hz. I have a little fender amp that sounds shockingly good considering how small and cheap it is. I played a P-bass through the gain channel, and it sounded snarly as hell.

The snarly bass begged for crash cymbals, which screamed for icy piano… and the song sort of accidentally wound up with a tacky Nu Metal breakdown in the middle. Oops.

(If you’d like, here’s the full song in this unfinished nu metal state.)

At the end of the weekend, I sent the song to my friend Lu — maybe they’d want it for their video?

I didn’t release it. I kept working on it for a while. Trying to carve away sections where my playing was trash, or I’d made instrument choices that weren’t working.

Lu used it in a video after all (along with another “song” I made by chopping up a bunch of my older songs and scrambling them together).

Over the following months, whenever I had some time alone, I added more instruments. Bass clarinet. Tuba. A little cheapo Casio. Shakers. Melodica. Recorder.

I wanted the song to have lyrics and a main vocal line. But the shrinking meant something to me, so the lyrics would need to mean something, and I… don’t do that anymore.

So now I’ve given up on it. The song is not finished. It’s abandoned. But I’m okay with that.

The mix is trash. The day I released it, right before the final render, I made the organ too loud at the start, and I’m going to resent that forever. The drums sound fake. The guitar playing is sloppy. The A-section desperately needs a countermelody (which… was supposed to be the vocals). The recorder is too loud. The B-section (that used to be Nu Metal) feels stilted and vacant. The later part is dull, but yet the ending comes too quickly. The melodica is cheesy. The recorder is cheesy. The main melody is cloying and predictable and childish. None of the section transitions flow. The song sucks.

The 2nd A-section, at 2:23, is… fucking great. It makes me so happy. It was a total accident, too. Everything just worked together, right from the get go, totally unplanned. Sure, it’s just a drone on E, but who cares, it grooves. And that trashy china-esq crash cymbal that keeps coming in and out (at double duration each time — eighth notes, then quarter, half, whole, breve) sits perfectly in the mix. See, look what happens when I pull it out…

…it sounds like junk by itself! But it just melts into place with everything else around it. I’ve never used this cymbal before because it sounds like junk, so I had no idea it could do this. And you can’t quite perceive it, but there’s a shaker doubling that cymbal, too. This is called “masking”, and I love doing it.

(Someday I'll tell the story of how I got all these cymbals.)

There’s an imperceptible little draaag where all the instruments slow down a tiny bit, and then they all race ahead to catch up to the beat. I did it by accident when recording the very first drum track, and then just repeated the same mistake in every layer that followed. The drag is so small, but it feels so weirdly good to just stretch out how you feel the moment passing. The interplay between the space and your body.

And the song, it almost does one more thing. A very special thing. A thing that I always, always wanted the shrinking to do. I’ve been trying to make it do. For over a decade. For 14 years now. And a half. Almost fifteen. Years. Now.

There are things you assumed were constant, but what if they aren’t?

My goal for the shrinking is that it should mean something. When something shrinks, or it grows, it should say something. You should feel something. If the shrinking and growing doesn’t express anything, if it’s just a cool trick, that’s wrong. It’s wrong.

A Shrinking Feeling, the game, was going to use its constant shrinking to say something: “if you leave a little thing alone, a little nagging worry, a little problem, it’ll grow and grow until you can’t deal with it any more… but you can slip away from it, and leave it behind… and that’s just fine. you keep changing. you’ll never stop changing. the you that was threatened by that thing is gone. there’s a new you now.”

I haven’t figured out what the shrinking music should say. I had something in mind for this song, that I could say through some lyrics, but… I don’t do that anymore.

But I need to do one thing first, with this music, to eventually be able to say something with it: I need to know I can make you not notice the shrinking. It should feel natural. It’s a means to an end, not an end in itself.

Am I a good enough musician to pull that off? Probably not. I didn’t quite get there, this time. But I think I got close. For most of the song, it’s so smooth, but then at moments it’s jarring. But when I tap my fingers together, keeping time, speeding up, the smooth bits and the jarring bits feel the same. I came so close with this one.

I’ll probably come back to this idea again. I don’t want to make music that only speeds up forever, or slows down forever. I want to find a way to make the tempo change, and the change of tempo change, and the change of the change of tempo change. (That’s why the song is called “Jerk” — I’m a jerk because I didn’t do the thing.)

And unlike the tower game, (and the other ideas we had, some of which have appeared elsewhere), I haven’t seen anyone do a shrinking game. So I’ll probably come back to that too.